My long-time colleague Alan McIntosh recently retired, stepping down from his role as Chief Investment Strategist at Quilter Cheviot and bringing down the curtain on a fund management career spanning over four decades. Much has changed since Alan took his first tentative steps into the industry in 1982 but at the same time many of the sound investing principles he adheres to remain as valuable as ever, not only withstanding the passing of time during his career but attracting a greater body of supporting evidence.

James Hughes and I recently had the pleasure of sitting down with Alan to reflect on his career — you can tune in to the podcast here. As has been my experience throughout the 10+ years I worked alongside Alan, he was full of wisdom and wit. To hear Alan’s reflections on his career do listen to the podcast in full.

I have attempted to summarise the conversation by highlighting three valuable maxims — not just for investing but in many walks of life — below.

Don’t be too clever!

One of the very first lessons Alan learned in his career was to no try and be too clever. Counterintuitive as it sounds, this is a common weakness among investors and especially prevalent in those lacking experience.

Alan started as a trainee US fund manager in 1982, a time when working conditions were quite different. There were no emails and communication with those not in the same room was via telephones or fax machines. Still, there were similarities to the current investing environment, most notably a keen interest in US tech companies with a flurry of IPOs based on the rapidly growing chip industry.

One of Alan’s early recommendations was a discount retailer called K-mart. He shared his views with a peer at another firm during a conference but was told that they preferred Walmart. Upon returning to the office he relayed the conversation with his boss, who dismissed the Walmart recommendation saying that everyone was keen on the stock and K-mart traded on a significantly cheaper valuation. Six months later K-mart had gone out of business and Walmart went on an incredible growth journey to reach a market valuation of around US$500bn.

Parallels can be drawn between the current market environment where US stocks, and the so-called “Magnificent Seven” in particular, are trading at a premium. As we’ve discussed previously on the podcast, there is arguably good reason for this as leading US firms have demonstrated relatively higher growth in recent years and are placed front and centre of the burgeoning Artificial Intelligence industry.

Avoiding mistakes is key

Focus on avoiding clangers rather than picking the next winner, as Alan puts it. Linked to the first point, for many there is a natural inclination to spend most of the time trying to find the hot new thing rather than focusing on what could go wrong. A good lesson for investors is to spend more time seeking to avoid major mistakes as they are often just a big a driver, if not bigger, of long-term returns than the things done right.

Alan reflects on his experiences during the 1987 stock market crash, know to some as Black Monday, when US equities fell over 20%. There had been a hurricane in the south of England the Friday before which meant that many brokers couldn’t get to their desks — and remote working was still decades away!

Alan was still based in Edinburgh at the time so was unaffected, although he could not get hold of the brokers. After the London market had closed on Friday Alan received a call from a US broker around 5:30pm, offering a large chunk of a stock at a 5% discount. Alan bought the stock and the following trading day, Black Monday, was the largest percentage drop in the history of US benchmarks. The stock fell over 20% and Alan swiftly rung up a broker to exit.

Another anecdote relating to this came from the 2007-08 financial crisis. Alan had plated a key role in setting up Cheviot in 2006 and felt the business was just getting established when Lehman Brothers collapsed. A senior colleague at the time had a prominent role at RBS, with a long background in the banking sector.

The colleague was adamant that the situation was just a liquidity crisis and that in time it would sort itself out, persuading Alan to hold on to a position in RBS. Ultimately it became clear that it was not just a liquidity crisis but a solvency crisis too and RBS failed, being taken over by the UK government. Alan says from this he learned that even people you believe should know things inside out, often do not.

Big picture: up and to the right — most of the time.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

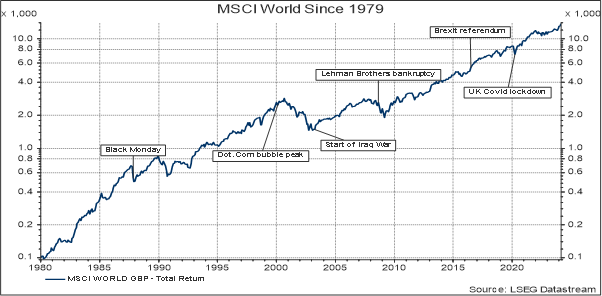

Global stocks have enjoyed a strong run higher over the last 45 years, despite a number of major perceived setbacks along the way. Don’t be too clever, avoid mistakes and you’ve had a strong prevailing tailwind at your back.

Circumstances matter

While this is evidently true, it is often overlooked by many when assessing the potential impact on the markets. Alan refers to the differing inflationary impact of Quantitative Easing (QE) in response to the Covid-19 pandemic compared to the 2007-08 financial crisis. There were many calls fearful that QE would fuel a surge in inflation when it was introduced at scale in the US and UK, in 2008 and 2009 respectively.

However, Alan thought differently due to his background studying the Chicago school of economics. There had been a sharp drop in money supply as the velocity of circulation collapsed, a similar dynamic to that leading to the 1930s depression. Alan describes the situation in layman’s terms as a bucket with a hole in. You need to keep putting water into the bucket just to keep the water level steady. The hole ensures that it will not overflow. If you do not fill it up, the water level will drop and empty the bucket, leading to a depression.

More recently the situation was quite different. The introduction of QE during the pandemic came alongside a huge fiscal stimulus (absent in 2008-09) comparable to the Marshall plan to redevelop post-war Europe. Unlike in 2008, supply was substantially constrained while demand was fuelled. This led to sharp increases in the money supply as velocity of circulation surged. Simply put, there was too much money chasing too few goods.

Looking back on both occurrences with the benefit of hindsight the use of QE in 2008-09 was the required response but was unnecessary in 2020. The fiscal response and swift re-opening of the economy meant that it was excessive, leading to the subsequent surge in inflation.

Another example Alan highlights is the difference between the current hype surrounding technology stocks and that which occurred around 25 years ago around the turn of the millennium. There were many similarities back then to the current environment, but it is not a parallel.

Alan was working on a UK desk in the late 1990s, watching the speculative frenzy in US tech companies reach fever pitch while so-called “old economy” stocks — many of which made up his investable universe — underperformed. There was a rush to sell stocks like Unilever as people chased the hot new thing.

A key difference between then and now is that the dotcom bubble contained lots of surging stocks for unprofitable companies whereas these days the Magnificent Seven are producing substantial free cash flows, have significant cash piles and dominant market positions with high barriers to entry. Indeed, some of the attraction to these stocks was that they were perceived as safe places to invest in uncertain economic times, as their businesses have extremely strong competitive positions and fairly inelastic demand. Even if we experienced a sharp economic contraction would that many people stop using products from Microsoft or Apple or stop using Google and Facebook. In fact, the market position of these is so strong that arguably the greatest threat is regulatory action to curb

Message for new investors

Alan concluded our discussion by offering some wise words of advice for those setting out in the industry as investment managers. A natural sense of curiosity has been one of the main drivers of success during Alan’s distinguished career. A genuine desire to learn, acting like a sponge in soaking up information and trying to know a little about a lot of things are all sound principles that help an investor.

There should be no fear of higher real rates as although it marks a significant shift from the investment environment of the last 15 years, history shows that it is not prohibitive to strong equity returns. From 1982 to 2000, a period of nearly entirely positive real rates, US stocks averaged around 17% annual returns. You simply do not need near zero rates for high equity returns.

In some ways higher real rates are even positive in themselves, offering proper price discovery and a real discount rate that reveals how capital should be allocated across different asset classes. It has no doubt been painful getting here, but from now on with a reasonable time horizon, say 7+ years, it’s a great time to start.

Best investments

Alan singles out Renishaw as probably his best individual investment. He bought in the early 1980s when it was a small-cap stock and is still holding it. From a tactical perspective, increasing gold allocations ahead of the Brexit vote stands out as another very good move. Gold provided something of a safe haven during the aftermath of the victory for leave, but it was mainly the currency effect that meant it was such a good move for UK investors. As sterling fell so much, it meant that investors could buy back in at much lower levels.

All in all we have much we can learn from studying history and from the experiences of those who have been investing for many decades and I would implore you to watch/listen if you get a chance.

This is a marketing communication and is not independent investment research. Financial Instruments referred to are not subject to a prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination marketing communications. Any reference to any securities or instruments is not a personal recommendation and it should not be regarded as a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities or instruments mentioned in it

--

The MSCI information may only be used for your internal use, may not be reproduced or redisseminated in any form and may not be used as a basis for or a component of any financial instruments or products or indices. None of the MSCI information is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such. Historical data and analysis should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of any future performance analysis, forecast or prediction. The MSCI information is provided on an “as is” basis and the user of this information assumes the entire risk of any use made of this information. MSCI, each of its affiliates and each other person involved in or related to compiling, computing or creating any MSCI information (collectively, the “MSCI Parties”) expressly disclaims all warranties (including, without limitation, any warranties of originality, accuracy, completeness, timeliness, non-infringement, merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose) with respect to this information. Without limiting any of the foregoing, in no event shall any MSCI Party have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, punitive, consequential (including, without limitation, lost profits) or any other damages. (www.msci.com)

Subscribe to Taking Stock - Diary of an Investment Manager

Get the inside view from Quilter Cheviot Investment Manager, Jonathan Raymond, in his fortnightly diary.