What has been driving the moves?

In the UK, the short end of the curve is being dragged lower by the BoE cutting interest rates while concerns regarding inflation and fiscal sustainability, alongside structural market dynamics, are boosting long end yields. One way of monitoring the steepness of a bond curve across maturities is to look at the difference between two points over time, e.g. the spread between the 10-year yield and the 30-year yield. This spread has recently increased significantly, hitting a 10-year high.

30-year gilt yields have opened up a spread over the 10-year and 2-year yields

Source: LSEG Datastream, Quilter Cheviot Limited 01/09/2025.

These figures refer to the past and past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Looking at the long end, the rise in inflation, debt sustainability concerns and market dynamics have all had an impact.

Inflation

The UK consumer price index rose more than expected to 3.8% in July and is likely to rise further due to increases to national insurance and the minimum wage, as well as higher energy and food costs. This can also impact the short end, constraining the BoE’s ability to cut interest rates further. The BoE has been lowering rates to support economic activity after raising them sharply during 2022 and 2023.

UK inflation is rising but well below the 2022 peak

Source: LSEG Datastream, Quilter Cheviot Limited 01/09/2025.

These figures refer to the past and past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Fiscal concerns

At the Autumn Budget 2024 Rachel Reeves announced plans to increase government borrowing by £30bn per year and this increase means more issuance in long-dated bonds. This increase was slated to be used for capital investments that would boost long-term growth prospects but in the short-term growth remains anaemic. Slower growth means lower tax receipts than expected and additional pressure on the public purse after Rachel Reeves committed to balancing day-to-day spending. The shortfall in this balance and seeming inability to make substantial spending cuts (e.g. U-turn on the winter fuel allowance and welfare reform) has damaged fiscal credibility and raised expectations of further significant tax rises in the forthcoming budget.

The UK has run a persistent budget deficit for 20 years

Source: LSEG Datastream, Quilter Cheviot Limited 01/09/2025.

These figures refer to the past and past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

International effects

The UK is not alone in facing fiscal challenges, and at least part of the increase in gilt yields can be attributed to events across the Atlantic. US President Donald Trump has brought a number of big policy changes in this regard, such as the implementation of far higher trade tariffs on imports and the passing of the so-called “Big, Beautiful Bill” which is expected to increase the US deficit by US$3.4tn through 2034, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Trump’s repeated and brazen attacks on the Federal Reserve’s independence have also played a role.

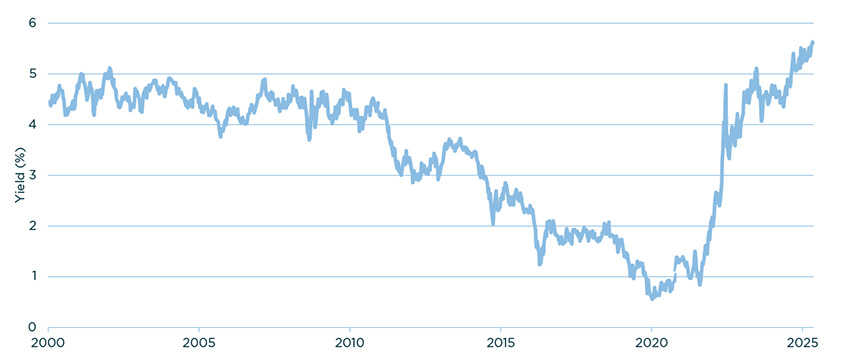

The relationship between US and UK bonds can be seen by looking at the change in the respective 30-year yields from the start of 2022 through 1 September 2025. The US 30-year yield has risen from 2.12% to 4.93% while the UK 30-year yield has increased from 1.29% to 5.64%.

The UK 30-year yield has moved above the US 30-year yield

Source: LSEG Datastream, Quilter Cheviot Limited 01/09/2025.

These figures refer to the past and past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

The spread between the two 30-years (UK-US) is one way to clearly look at the change in this relationship. It has increased from -0.83% at the start of 2022 to 0.71%. While this is a notable increase, this spread is still around the highest levels seen in recent years and has not increased particularly sharply in the last few months.

The UK-US 30-year yield spread has risen but is not above peaks seen in recent years

Source: LSEG Datastream, Quilter Cheviot Limited 01/09/2025.

These figures refer to the past and past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

There are also government debt cost concerns elsewhere, with French and Japanese bond yields making headlines for the wrong reasons in recent weeks. In Japan, the sharp rise has caused concern after a prolonged period of near-zero interest rates and a persistent lack of inflation.

Market dynamics

Demand for gilts among market participants, not for the macroeconomic reasons listed above, can also play a part. Defined Benefit pension schemes have long been significant players in the long-end of the gilt curve, buying bonds to hedge the risk of their commitments. As Defined Benefit schemes become less common there is a notable drop from this buyer base. Without the pension funds, the buyer base for long-dated gilts has arguably become more fickle than for shorter-dated gilts which attract a wider range of investors.

Supply is also rising. On top of the additional issuance to fund government borrowing, the BoE are unwinding some of their bond holdings through a process known as Quantitative Tightening. The BoE built up a stockpile of bonds during the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic and have around £620bn of gilt holdings. The OBR currently assumes active sales of £48bn every year until the end of its forecast (2029-30), on top of varying levels of passive reduction as gilts mature.