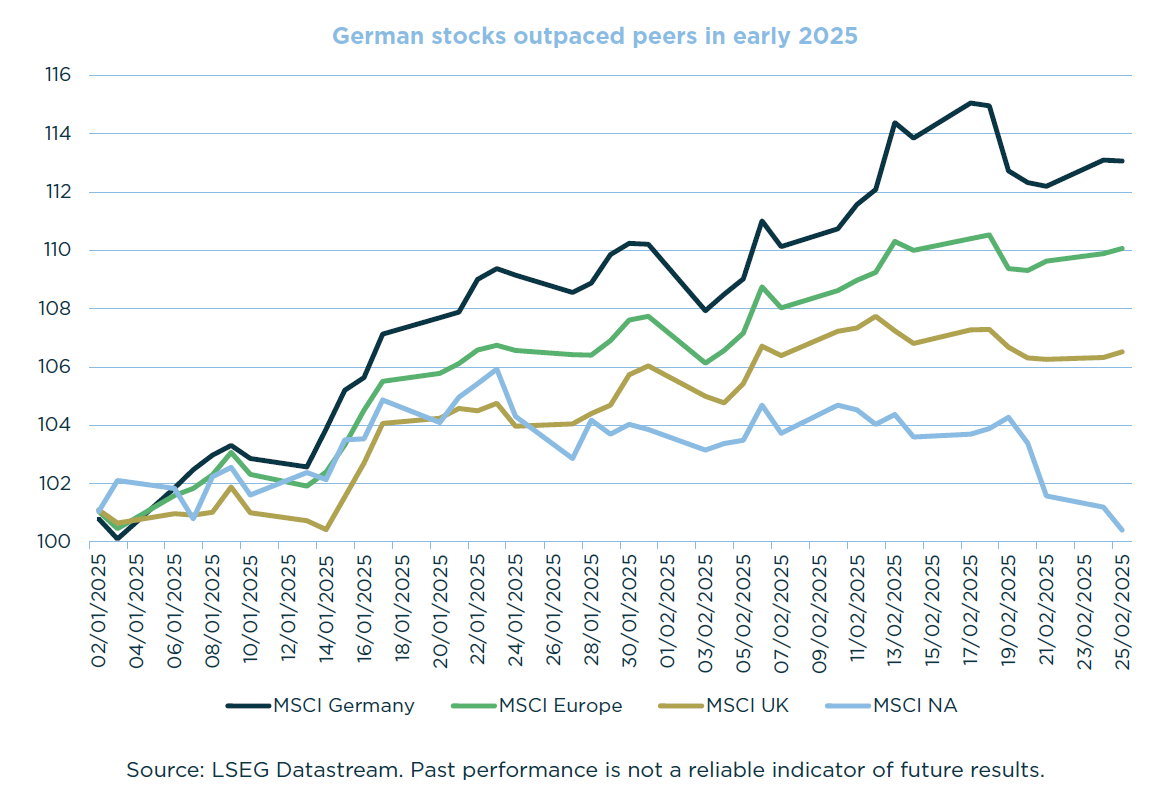

The performance of German stocks in recent months shows that political uncertainty is not necessarily a negative for investment performance. It depends on what the uncertainty may bring. While the incoming coalition is an unknown entity to some extent, it is still seen as likely being less disruptive than a coalition involving the far-left or far-right parties. The sequence of events that brought down the last government also suggesting the incoming government may well be more open to fiscal stimulus, which after years of sluggish economic growth could provide a much-needed kick start to the EU’s largest economy.

This also shows the potential importance of relative valuations and sentiment. Following Donald Trump’s election victory, a large swathe of money managers saw the US extending its run of outperformance and European stocks continuing to lag. With sentiment on Europe downbeat, it does not necessarily require an abundance of positive news to turn the tide.

It is still early days, but recent market moves are encouraging and once more demonstrate the value in geographic diversification when investing. With hopes raised that the war in Ukraine may soon come to an end and the European Central Bank expected to cut rates further and faster than the Federal Reserve and Bank of England the fundamental picture is shifting more favourably towards European stocks.

1 GDP international comparisons: Economic indicators - House of Commons Library